By Robert Zeliger

President Ahmadinejad: pressure from all sides

Even by Iranian political standards, the last few days have been dramatic. A dozen people close to President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and his cabinet have reportedly been arrested since last week on "financial charges." Then on Wednesday, the embattled president came out swinging more directly and forcefully than he has done before -- warning his enemies to back off.

President Ahmadinejad: pressure from all sides

Even by Iranian political standards, the last few days have been dramatic. A dozen people close to President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and his cabinet have reportedly been arrested since last week on "financial charges." Then on Wednesday, the embattled president came out swinging more directly and forcefully than he has done before -- warning his enemies to back off.

"I consider defending the cabinet as my duty," he told reporters. "The cabinet is a red line and if they want to touch the cabinet, then defending it is my duty.... From our point of view these moves and pressures are political...to put pressure on the government."

Ahmadinejad is in fact getting pressure from seemingly all corners, including the judiciary, the parliament, and most troubling for sure, the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei -- the very man who so publicly placed his eggs in the Ahmadinejad basket two years ago.The pressure is so bad that the summer of 2011 may make Ahmadinejad wistful for the halcyon days of 2009, when all he had to worry about were a few hundred thousand reformists marching in Tehran, demanding his removal.

Below is a guide to Ahmadinejad's many headaches. The Supreme Leader

Ahmadinejad is Khamanei's golden boy no longer. The Supreme Leader sent a major signal to the president back in April when a dispute over the sacking of the intelligence minister played out in public. Ahmadinejad forced the minister to resign. Khamanei objected and insisted that he stay on. Ahmadinejad responded by staging a mini-boycott, refusing to come to work for 11 days.All hell broke loose, said Abbas Milani, an Iran scholar at Stanford's Hoover Institution.

"Khamanei unleashed all his forces, so to speak," he said. "There was a ferocious attack on Ahmadinejad in parliament." Talk of impeachment intensified, Milani said. Eventually Ahmadinejad came back to work, chastened.His enemies took notice -- sensing he no longer enjoyed the unwavering support of the Supreme Leader.

There have even been public indications of a thaw between Khamanei and two other prominent but controversial figures in Iranian society -- former presidents Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani and Seyyed Ahmad Khatami.Just yesterday, a site close to the Revolutionary Guards and the Supreme Leader did something it hasn't in the past two years since the disputed election -- it referred to Rafsanjani using his honorific, Ayatollah, according to Milani.

Recently, Khatami spoke about the need for forgiveness on all sides in the 2009 presidential dispute, saying both sides have committed mistakes but that they should put it behind them.The man being left out of this new warmth? Ahmadinejad.

"Khamanei feels isolated," Milani said. If he decided to get rid of Ahmadinejad and bring Rafsanjani back into the fold, he'd get a new boost of clerical support from the men aligned with Rafsanjani.The Parliament and Judiciary

Last week, members of parliament actually booed Ahmadinejad -- an act that the Supreme Leader said went too far. The parliament has certainly become emboldened against the president -- launching impeachment proceedings against his foreign minister and rejecting the president's nominee to the newly created (and totally insignificant) post of sports minister.Meanwhile, the judiciary, which is headed by the brother of the speaker of parliament, has gone after aides and cabinet ministers close to Ahmadinejad.

Critics say Ahmadinejad is trying to groom his controversial chief of staff, Esfandiar Rahim Mashaei, to take over for him after his legally mandated two terms are up in 2013 -- a blatant power grab. Mashaei, himself a lightning rod for criticism, has been called everything from a secular nationalist opposed to clerical rule to a "deviant current," who has used spell-casting powers to bewitch Ahmadinejad. He is also hated for saying back in 2008 that Iranians are "friends of all people in the world -- even Israelis."In both the judiciary and the parliament, things are going to get much worse before they get better for the president, according to Farideh Farhi, a researcher at the University of Hawaii in Honolulu.

The chief prosecutor has said there will be more arrests coming. And in the parliament, they are inching closer and closer to impeaching him -- though it's likely Khamanei has given instructions to slow down, at least for now.The Economy

Ahmadinejad's old foe, the economy, isn't giving him any more comfort these days, despite an upbeat assessment by a recent IMF mission to Tehran, which noted "structural reforms" related to Iran's subsidy program that reduced annual inflation from 25.4 percent in 2008/2009 to 12.4 percent in 2010/2011, according to an IMF press release. Still unemployment hovers near 15 percent and analysts say the picture is far from rosy."There are many, many serious economic problems on the horizon," said Milani. He cited the embargo on trade as having a serious pinch. "And every indication is it's going to get worse."

Ahmadinejad had been able to keep important segments of his constituency happy by doling out healthy subsidies, such as cash payments to the poorest segments of society. But those programs are being cut back, because there's less money to go around. And some analysts say that as the pie shrinks, the fighting over who gets what slice, is intensifying. The Revolutionary Guards, for example, have a vast business empire that spans the construction, telecommunications, and energy sectors, and gives them financial clout, something they don't want to lose even as Western sanctions targeting their interests continue to pinch harder.

For people looking for someone to blame, Ahmadinejad offers an easy target, due to his past mismanagement of the economy, Milani said. The neighborhood

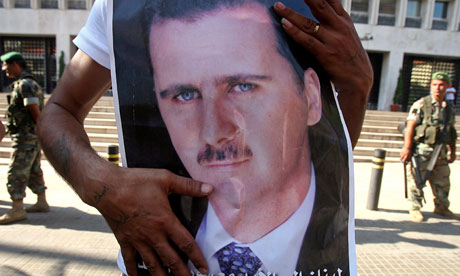

Despite the fall of one of Iran's most vocal antagonists in the region -- Hosni Mubarak -- and the ill-fortunes of many others, when Ahmadinejad looks beyond his borders there's not a lot to smile about these days. The biggest worry is Syria -- Iran's only real ally in the region -- where the regime of Bashar al-Assad is struggling to survive in the face of a massive, and sustained, uprising.

"If Syria goes then they are really left isolated," said Milani. A second concern is the increasing assertiveness on the part of Sunni Gulf Arab states, which have become more openly united against Iran.

"They are challenging them, because they perceive Iran to be in a weaker position," said Milani.

One example is Bahrain, into which the Saudis sent troops to help the Sunni royal family crush a largely Shiite uprising. If Iran was in a more powerful position, Milani said, they would have raised hell.All this adds up to a lot of headaches for a man who isn't characteristically prone to self-doubt -- at least not in public. Yet, Ahmadinejad's many chickens seem to be coming home to roost.

"My sense is we are already in a post-Ahmadinejad era," said Farhi. "The question is no longer will he become a Putin-type figure. The question is now whether they will let him stay for two more years or get rid of him sooner."This commentary was published in The Foreign Policy on 01/07/2011