On the day the people decided to sever their final links with the days of the pharoahs, the rebirth of a nation began

By Ayman Nour and Wael Nawara

This commentary was published in The Guardian on 05/02/2011

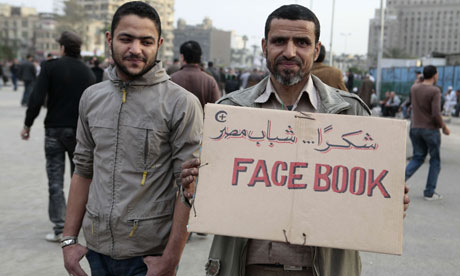

25 January is a date that will be forever remembered in Egypt. That was the day when the Egyptian people decided to end the country's last pharaonic dynasty with a people's revolution. Egyptians, it seems, were ashamed that Tunisians did it first and were determined to have their revolution too. Young Egyptians joined the "Khaled Saeed" Facebook group to launch the call for an uprising against tyranny, oppression, torture, corruption and injustice. The group was named after a young Egyptian man beaten to death by police.

That call was echoed on other Facebook groups, on blogs and on Twitter. El Ghad and a number of youth protest movements embraced the call from an early stage and started to mobilise support throughout the country. Many sceptics took the view that you cannot set a date for revolution, but although Egyptians are not the most punctual of people, this was a date they kept.

On 25 January, Egyptians took to the streets in almost every major town and city. The police tried to crush the protests, but unarmed people stood firm against water cannons, armoured carriers and teargas. Three days later, on the "Friday of rage", more than a million Egyptians took to the streets in support of the uprising. Anti-riot police used maximum force but finally had to retreat – and then they disappeared altogether, from Cairo and other major cities, in what appeared to be a conspiracy to plunge the country into chaos.

The army had to step in and were immediately embraced by protesters, who took photos with them and climbed on to their tanks. Mubarak came on TV that evening, offering a government reshuffle and warning of chaos. The protesters were disappointed and have vowed to remain in protest until their demands are met.

This is a revolution of the people. After eight days of protests, Mubarak started to get the hint – that he is no longer wanted as a president by his own people. The president's termination letter has been sealed by millions of Egyptians. After 30 years of ruling Egypt, the 83-year-old man has clearly become detached from reality.

After the November elections last year, when the ruling National Democratic Party (NDP) "won" more than 90% of the seats amid reports of widespread fraud and irregularities, the opposition National Assembly for Change developed what is now known as the people's parliament – a sort of shadow parliament with 100 members from various opposition parties and movements in addition to independents. The people's parliament elected a committee of 10 members to start a dialogue with the regime in order to put people's demands into action.

The demands of the protesters were beautifully crystallised in two chants: "The people want the regime down" and "Bread, freedom and human dignity". In political terms, the first demand relates to dismantling the authoritarian regime and installing democracy in Egypt. This means breaking down a culture of corruption emodied in the ruling NDP party, and restructuring the state security police to focus on criminal activities rather than meddle with the political process in defence of the status quo.

The protesters also demanded the dissolution of both chambers of the parliament as well as local councils, all of which were elected by a theatrical political process controlled by the regime and its security apparatus. For this to happen, the people's parliament proposed a peaceful transition of power through negotiating a national unity government of all political forces and protest movements in addition to the military. This transition government should oversee drafting a new constitution and laying out the rules of a political process that allows parties, civil society organisations and unions freely to emerge. This, in turn, can be followed by free and fair elections.

New political facts have emerged from this "revolution". The Egyptian people have demonstrated that they may be patient and peaceful to a fault, but they surely know how to make their voices heard at home and around the world. The way these spontaneous demonstrations took place and maintained a unity of demands, despite the blackout on mobile communication and stoppage of internet service, proves that a new collective conscience has been born in Egypt. In fact, Egypt itself has in these last few days been reborn.

Ayman Nour, leader of the El Ghad party, was imprisoned in 2005 by President Mubarak and released on health grounds in 2009.

Wael Nawara is a leading Egyptian writer.