The Berber people, known as Amazigh, find rare unity as they form one of the fronts taking on the might of the Gaddafi regime

By Moez Zeiton

"Did you know that this is the year 2961?" my driver asked as we drove along a tortuous road through the mountains. At first, I thought he was joking but he went on to explain that the Amazigh calendar started in 950BC.

As we stopped at each checkpoint, I strained to understand what he was saying to the local people, imagining that it was some odd dialect of Arabic – but I had no idea what any of the words meant.

This recent encounter opened my eyes to a long-neglected ethnic culture in my own backyard in Libya. The Amazigh people (also known as Berbers) are Numidian descendents and the indigenous people of north Africa. They can be found from the Canary Islands in the Atlantic (where they were expelled in the 15th-century Spanish conquest) to the Siwa oasis in Egypt.

The Amazigh of Libya are found mainly in the Jebel Nafusa region (the western mountains) which has become the third front in a three-pronged resistance movement against the rule of Muammar Gaddafi.

Since coming to power and attempting to take on the Nasserist mantle of Arab nationalism, Gaddafi had tried to Arabise the Amazigh of Jebel Nafusa. He attempted to erase their cultural identity by banning their language.

"Why can't we have our own identity?" one of the town's elders asked me. "In Britain, they have Welsh and Gaelic people each with their own unique identity which the British government supports. They even have some degree of political autonomy but we are not even asking for that. We just want to be able to teach our children about our culture and heritage."

Perhaps testament to the lack of development and neglect of the region is the 300km road from the Tunisian-Libyan border crossing of Dheiba-Wazin to the garrison town of Gharyan. "It's exactly like the Italians left it," one of the revolutionaries manning a checkpoint said, referring to the colonial era.

In fact, despite their lack of resources, the revolutionaries have done more to develop this road in the past few months than Gaddafi did in four decades. As we drove near Irheybaat the usual white lines in the centre of the road transformed into runway markings. On either side of the road, stood runway lights and at the end there was a windsock.

This improvised airport is being used for members of the National Transitional Council to visit the region and allow delivery of essential supplies (though nobody would confirm whether it had been used for military supplies).

The rich culture of the Amazigh has found a new lease of life since the uprising began. Not only that, but it has also acted as a unifying force for the region in the face of Gaddafi's troops.

"The revolution has brought us all together," remarked one local from Yefren, "We all had our tribal allegiances before, and it would be rare for anyone to eat from the same gasa'a (shared plate) as someone from another Amazigh town. Now Nalut, Kabaw, Jadu, Zintan, Yefren, al-Qalaa – we all eat in the same plate."

With this unity in hand, the Amazigh have managed to withstand a much better equipped and advanced mechanised force in Gaddafi's battalions. The remaining inhabitants of Yefren, Kikla and al-Qalaa told me how, for more than two months around April and May, they withstood the advance of government troops using their superior knowledge of the terrain.

In Yefren, they dug a huge trench through the main road leading in to the town. Government troops could not advance with their mechanised vehicles and an advance with infantry was not an option for Gaddafi's men due to their poor morale and motivation.

I met a 15-year-old boy, Sifax, who was one of those protecting the town of during the siege. He was wearing a Real Madrid football shirt with the name of Zinedine Zidane – one of the best-regarded footballers of all time – printed on the back. "You do know that he is Amazigh, right?" he asked me.

He then proudly showed me the weapon he used to defend his town during the two-month siege – a 1940s-era Italian Carcano rifle handed down from his grandfather.

The Amazigh people are a close-knit community and while it would be foolish to assume that nobody in Gaddafi's ranks that speaks their language, it would be difficult for a non-Amazigh to infiltrate their ranks – and this provides them with extra security.

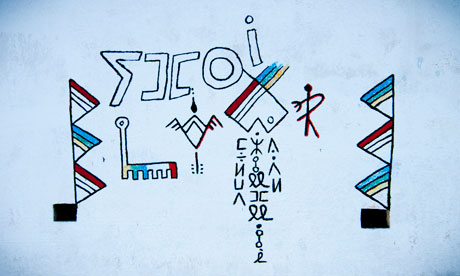

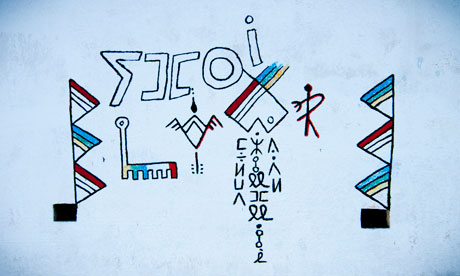

The Tifinagh letters of the Amazigh language can be seen in inscriptions and graffiti all over the Nafusa region in defiance of the regime. The first book to appear in the Amazigh language since 17 February is a children's alphabet book published by the newly established National Foundation for Amazigh Culture in Yefren. And every liberated town in the Nafusa region has its own media centre.

The old mathaba building in the centre of Yefren was where Gadaffi's much-feared elite guards were stationed. It was the place where political opponents were persecuted and even killed. Now every room has been transformed into an art exhibition of Gaddafi's crimes against the Libyan people with murals dedicated to the martyrs of the capital, Tripoli.

The Amazigh population have found a new sense of identity that they hope to express freely in a democratic Libya. Different ethnic groups and cultures in a country add to its value and should not be seen as a reason for friction or disharmony. On the contrary, it is the blending of these different cultures that will foster good relations and understanding between people.

In the three-pronged assault on Gaddafi from Benghazi to Misrata to Jebel Nafusa, each region has had its fair share of casualties and sacrifices. Recalling the long siege of Misrata and the sacrifice of hundreds of lives there, many Libyans now refer to its people as "the lions of Misrata". By the same token, the Amazigh are surely the tigers of Jebel Nafusa.

-This commentary was published in The Guardian on 06/08/2011

- Moez Zeiton is a British-Libyan doctor and activist

By Moez Zeiton

Tifinagh script is a powerful symbol of Amazigh resistance to the Gaddafi regime. Photograph: Moez Zeiton

"Did you know that this is the year 2961?" my driver asked as we drove along a tortuous road through the mountains. At first, I thought he was joking but he went on to explain that the Amazigh calendar started in 950BC.

As we stopped at each checkpoint, I strained to understand what he was saying to the local people, imagining that it was some odd dialect of Arabic – but I had no idea what any of the words meant.

This recent encounter opened my eyes to a long-neglected ethnic culture in my own backyard in Libya. The Amazigh people (also known as Berbers) are Numidian descendents and the indigenous people of north Africa. They can be found from the Canary Islands in the Atlantic (where they were expelled in the 15th-century Spanish conquest) to the Siwa oasis in Egypt.

The Amazigh of Libya are found mainly in the Jebel Nafusa region (the western mountains) which has become the third front in a three-pronged resistance movement against the rule of Muammar Gaddafi.

Since coming to power and attempting to take on the Nasserist mantle of Arab nationalism, Gaddafi had tried to Arabise the Amazigh of Jebel Nafusa. He attempted to erase their cultural identity by banning their language.

"Why can't we have our own identity?" one of the town's elders asked me. "In Britain, they have Welsh and Gaelic people each with their own unique identity which the British government supports. They even have some degree of political autonomy but we are not even asking for that. We just want to be able to teach our children about our culture and heritage."

Perhaps testament to the lack of development and neglect of the region is the 300km road from the Tunisian-Libyan border crossing of Dheiba-Wazin to the garrison town of Gharyan. "It's exactly like the Italians left it," one of the revolutionaries manning a checkpoint said, referring to the colonial era.

In fact, despite their lack of resources, the revolutionaries have done more to develop this road in the past few months than Gaddafi did in four decades. As we drove near Irheybaat the usual white lines in the centre of the road transformed into runway markings. On either side of the road, stood runway lights and at the end there was a windsock.

This improvised airport is being used for members of the National Transitional Council to visit the region and allow delivery of essential supplies (though nobody would confirm whether it had been used for military supplies).

The rich culture of the Amazigh has found a new lease of life since the uprising began. Not only that, but it has also acted as a unifying force for the region in the face of Gaddafi's troops.

"The revolution has brought us all together," remarked one local from Yefren, "We all had our tribal allegiances before, and it would be rare for anyone to eat from the same gasa'a (shared plate) as someone from another Amazigh town. Now Nalut, Kabaw, Jadu, Zintan, Yefren, al-Qalaa – we all eat in the same plate."

With this unity in hand, the Amazigh have managed to withstand a much better equipped and advanced mechanised force in Gaddafi's battalions. The remaining inhabitants of Yefren, Kikla and al-Qalaa told me how, for more than two months around April and May, they withstood the advance of government troops using their superior knowledge of the terrain.

In Yefren, they dug a huge trench through the main road leading in to the town. Government troops could not advance with their mechanised vehicles and an advance with infantry was not an option for Gaddafi's men due to their poor morale and motivation.

I met a 15-year-old boy, Sifax, who was one of those protecting the town of during the siege. He was wearing a Real Madrid football shirt with the name of Zinedine Zidane – one of the best-regarded footballers of all time – printed on the back. "You do know that he is Amazigh, right?" he asked me.

He then proudly showed me the weapon he used to defend his town during the two-month siege – a 1940s-era Italian Carcano rifle handed down from his grandfather.

The Amazigh people are a close-knit community and while it would be foolish to assume that nobody in Gaddafi's ranks that speaks their language, it would be difficult for a non-Amazigh to infiltrate their ranks – and this provides them with extra security.

The Tifinagh letters of the Amazigh language can be seen in inscriptions and graffiti all over the Nafusa region in defiance of the regime. The first book to appear in the Amazigh language since 17 February is a children's alphabet book published by the newly established National Foundation for Amazigh Culture in Yefren. And every liberated town in the Nafusa region has its own media centre.

The old mathaba building in the centre of Yefren was where Gadaffi's much-feared elite guards were stationed. It was the place where political opponents were persecuted and even killed. Now every room has been transformed into an art exhibition of Gaddafi's crimes against the Libyan people with murals dedicated to the martyrs of the capital, Tripoli.

The Amazigh population have found a new sense of identity that they hope to express freely in a democratic Libya. Different ethnic groups and cultures in a country add to its value and should not be seen as a reason for friction or disharmony. On the contrary, it is the blending of these different cultures that will foster good relations and understanding between people.

In the three-pronged assault on Gaddafi from Benghazi to Misrata to Jebel Nafusa, each region has had its fair share of casualties and sacrifices. Recalling the long siege of Misrata and the sacrifice of hundreds of lives there, many Libyans now refer to its people as "the lions of Misrata". By the same token, the Amazigh are surely the tigers of Jebel Nafusa.

-This commentary was published in The Guardian on 06/08/2011

- Moez Zeiton is a British-Libyan doctor and activist