Mahmoud Ahmadinejad's disregard for the constitution has brought him up against both the supreme leader and parliament

By Massoumeh Torfeh

This commentary was published in The Guardian on 21/05/2011

This week the Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad took his challenge against the supreme leader, Ali Khamenei, to a new high by warning that Khamenei would be powerless without public support. "The leader's hands are tied without public support," Ahmadinejad told the state TV's channel 2. Questioning the sanctity of the supreme leader in this direct fashion goes against the grain of the Islamic republic, especially when uttered by the president and when it follows another episode of power struggle.

Ahmadinejad also confronted the conservative majority in parliament by rejecting its demand for a new committee to oversee the parliamentary elections due this winter. He insisted that no one other than the ministry of interior has the right to interfere in the elections.

In one week he reduced eight ministries to four, sacked four ministers, appointed a new deputy and named himself as caretaker oil minister without the due parliamentary procedures or consultation with the leader.

This escalating confrontation between the president and the leader on the one hand, and the president and the parliament on the other is causing new cracks at the leadership level, effectively creating a three-tier system. It is also causing further friction in conservative ranks, creating three major camps and several splinter groups.

The controversial Esfandiar Rahim Mashaei, who is Ahmadinejad's chief of staff, his main adviser and confidant, leads the president's team. They are the most rightwing conservatives; yet, because they are nonclerical and younger looking they seem bold in challenging the clergy.

Mashaei is demanding an "Iranian republic" rather than an "Islamic Republic" – apparently in an effort to attract the young who protested after the presidential elections of 2009. He presents himself as the theorist of a new school of thought praising the glories of Iran, and humanity, putting these above Islam.

On Wednesday he received authorisation to open a private university called the International Comprehensive University for Iranians – whatever that means. He is also said to be funding several new newspapers including the popular Haft e Sobh ("Seven in the Morning"). Designed to be modern and fashionable to appeal to the young, it covers gossip, music, film, cooking and sport. Yekshanbe Weekly and Tamasha daily are other papers launched allegedly by Mashaei who is keen on winning the youth vote in the presidential elections of 2013.

The conservatives are hitting back. They call Mashaei and his supporters the "misguided gang". Some like Faashnews ("Revealing News") close to Mohammad Hossein Safar-Harandy, a staunch supporter of the supreme leader, call Ahmadinejad and Mashaei "coup plotters". There are numerous articles in conservative papers accusing the group of being the new threat to the Islamic Republic. Even Ahmadinejad's guru, Ayatollah Mesbah Yazdi, criticised him on Thursday for undermining the leader for the sake of this group, and for grooming Mashaei to be the next president.

Oblivious to the conservative backlash, the president strengthened his team on Thursday by appointing another controversial deputy, Ruhollah Ahmadzadeh-Kermani, a close associated of Mashaei.

The more serious confrontation is taking place in parliament where majority conservative MPs are calling on Ahmadinejad to justify what they term as his "illegal" decisions. The parliament speaker, Ali Larijani, has demanded that recent changes to the ministries must first be approved by the parliament.

The president is also being ridiculed for appointing himself as caretaker oil minister in order to chair the 159th Opec meeting due on 8 June in Vienna. Some 12 MPs listing 50 cases of president's disregard for the constitution are threatening impeachment and the powerful Guardian Council has branded his oil ministry move as "illegal".

What would tilt the balance is the support of the powerful Revolutionary Guards. The chief commander of Revolutionary Guards has refrained from taking sides. He has, however, expressed his dislike of the "misguided gang". "There are many insiders concealing their opposition to the leader," General Mohammad Ali Jafari told Fardanews. "If they dare reveal their views they will be defeated". In what appears like a friendly warning to Ahmadinejad, he said it was not clear why "a popular politician" should continue to provide cover for this divergent group.

Ahmadinejad has proved to be obstinate both at home and in international affairs. Yet, it is hard to see how he can muster the required political strength to fight both the supreme leader and the parliament, especially when the conservative majority and the almost all clergy are against him, and the Revolutionary Guards are sounding disapproval.

As for the public support he is so keen on, it is also hard to see the public going behind him in opposition to the leader. It is even less likely that the progressive young will be swayed by Mashaei's flirtations. They are highly sceptical of anyone connected to Ahmadinejad.

Instead they are watching and waiting for the conservatives to fight their way out. They know that casting the new Iranian political mould will not be done by anyone inside the Islamist regime.

By Massoumeh Torfeh

This commentary was published in The Guardian on 21/05/2011

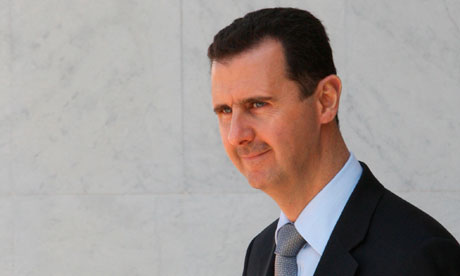

Iran's president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad has named himself as caretaker oil minister. Photograph: Murad Sezer/Reuters

This week the Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad took his challenge against the supreme leader, Ali Khamenei, to a new high by warning that Khamenei would be powerless without public support. "The leader's hands are tied without public support," Ahmadinejad told the state TV's channel 2. Questioning the sanctity of the supreme leader in this direct fashion goes against the grain of the Islamic republic, especially when uttered by the president and when it follows another episode of power struggle.

Ahmadinejad also confronted the conservative majority in parliament by rejecting its demand for a new committee to oversee the parliamentary elections due this winter. He insisted that no one other than the ministry of interior has the right to interfere in the elections.

In one week he reduced eight ministries to four, sacked four ministers, appointed a new deputy and named himself as caretaker oil minister without the due parliamentary procedures or consultation with the leader.

This escalating confrontation between the president and the leader on the one hand, and the president and the parliament on the other is causing new cracks at the leadership level, effectively creating a three-tier system. It is also causing further friction in conservative ranks, creating three major camps and several splinter groups.

The controversial Esfandiar Rahim Mashaei, who is Ahmadinejad's chief of staff, his main adviser and confidant, leads the president's team. They are the most rightwing conservatives; yet, because they are nonclerical and younger looking they seem bold in challenging the clergy.

Mashaei is demanding an "Iranian republic" rather than an "Islamic Republic" – apparently in an effort to attract the young who protested after the presidential elections of 2009. He presents himself as the theorist of a new school of thought praising the glories of Iran, and humanity, putting these above Islam.

On Wednesday he received authorisation to open a private university called the International Comprehensive University for Iranians – whatever that means. He is also said to be funding several new newspapers including the popular Haft e Sobh ("Seven in the Morning"). Designed to be modern and fashionable to appeal to the young, it covers gossip, music, film, cooking and sport. Yekshanbe Weekly and Tamasha daily are other papers launched allegedly by Mashaei who is keen on winning the youth vote in the presidential elections of 2013.

The conservatives are hitting back. They call Mashaei and his supporters the "misguided gang". Some like Faashnews ("Revealing News") close to Mohammad Hossein Safar-Harandy, a staunch supporter of the supreme leader, call Ahmadinejad and Mashaei "coup plotters". There are numerous articles in conservative papers accusing the group of being the new threat to the Islamic Republic. Even Ahmadinejad's guru, Ayatollah Mesbah Yazdi, criticised him on Thursday for undermining the leader for the sake of this group, and for grooming Mashaei to be the next president.

Oblivious to the conservative backlash, the president strengthened his team on Thursday by appointing another controversial deputy, Ruhollah Ahmadzadeh-Kermani, a close associated of Mashaei.

The more serious confrontation is taking place in parliament where majority conservative MPs are calling on Ahmadinejad to justify what they term as his "illegal" decisions. The parliament speaker, Ali Larijani, has demanded that recent changes to the ministries must first be approved by the parliament.

The president is also being ridiculed for appointing himself as caretaker oil minister in order to chair the 159th Opec meeting due on 8 June in Vienna. Some 12 MPs listing 50 cases of president's disregard for the constitution are threatening impeachment and the powerful Guardian Council has branded his oil ministry move as "illegal".

What would tilt the balance is the support of the powerful Revolutionary Guards. The chief commander of Revolutionary Guards has refrained from taking sides. He has, however, expressed his dislike of the "misguided gang". "There are many insiders concealing their opposition to the leader," General Mohammad Ali Jafari told Fardanews. "If they dare reveal their views they will be defeated". In what appears like a friendly warning to Ahmadinejad, he said it was not clear why "a popular politician" should continue to provide cover for this divergent group.

Ahmadinejad has proved to be obstinate both at home and in international affairs. Yet, it is hard to see how he can muster the required political strength to fight both the supreme leader and the parliament, especially when the conservative majority and the almost all clergy are against him, and the Revolutionary Guards are sounding disapproval.

As for the public support he is so keen on, it is also hard to see the public going behind him in opposition to the leader. It is even less likely that the progressive young will be swayed by Mashaei's flirtations. They are highly sceptical of anyone connected to Ahmadinejad.

Instead they are watching and waiting for the conservatives to fight their way out. They know that casting the new Iranian political mould will not be done by anyone inside the Islamist regime.