Despite great risks to them in a sexist society, thousands of women have stood up to demonstrate against President Saleh

By Nadya Khalife

This commentary was published in The Guardian on 07/05/2011

By Nadya Khalife

This commentary was published in The Guardian on 07/05/2011

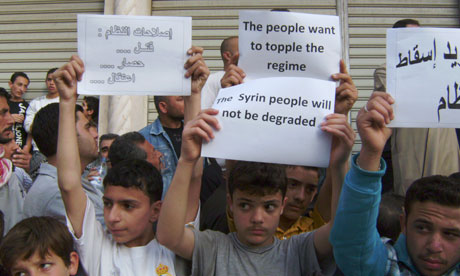

Women join a protest against President Ali Abdullah Saleh in the southern city of Taiz on 16 April. Photograph: Khaled Abdullah Ali Al Mahdi/Reuters

"Security forces in civilian clothes have threatened me with the jambiyya, not just during demonstrations, but everywhere I go," the protest leader and journalist Tawakkol Karman told me, describing the traditional dagger that Yemeni men wear strapped to their waists.

In the past, any mention of Yemen's women in the news media has usually been about two issues, neither of them positive. The first is that they are more likely than most women in the Middle East to die in childbirth, and the second that they are among the least empowered women in the world.

The second assumption has recently been shattered by the uprisings in Yemen.

Since the beginning of the protests, women like Karman have come out in great numbers to demonstrate against President Ali Abdullah Saleh, who has ruled in Yemen for more than 30 years. They have stood side by side with tens of thousands of Yemeni men to fill the city squares of Sana'a, Ta'izz, Aden, and other major cities, demanding his resignation.

Such has been the power of their presence that Saleh felt obliged to denounce women who join the protests as un-Islamic for demonstrating alongside men.

The protests have given women a chance to express their own concerns about their day-to-day struggles with the Saleh government, including their subordinate legal status as perpetual minors who require male guardians and the continued prevalence of harmful practices like child marriage.

Women have held their own demonstrations, but have also protested with their male counterparts, calling for democracy. Their courage has come at a cost: security forces and pro-government plain-clothes operators have threatened, verbally assaulted and attacked women protesters. At least 109 peaceful demonstrators or bystanders in Yemen have been killed since daily protests began in mid-February, and several hundred injured.

To be sure, many more male protesters have been targeted, but women in Yemen are particularly vulnerable to such attacks. Yemen is a traditional society, where women generally have low social status and are excluded from public life.

In 2010 a Freedom House report on women in the Middle East highlighted Yemen as one of only three countries in the region that had failed to make significant progress on women's rights in the preceding five years. Women have never held more than three seats out of 301 in the lower house of parliament. They do not have the same citizenship rights as men. And domestic violence is still not a criminal offence. Women's rights activists often face harassment.

In this context, many women are fearful about the consequences of participating in the uprising against Saleh. One young activist in Sana'a, who did not want to be named, told me she is one of several women she knows who don't tell their families they are going to the protests. She said the families have forbidden them from demonstrating, partly because they are worried about the women's safety, and partly because they know their reputations and honour are at stake.

The fears about their safety are not unfounded. On 27 April, unknown gunmen on motorcycles fired shots into the air outside the house of a prominent female activist, Bushra al-Maqtari, in Ta'izz, a city south of the capital. Maqtari said she had previously received anonymous verbal threats.

Another female activist from Ta'izz, a lawyer who also did not want to be named, told me about an incident she witnessed on 16 March when she went to pick up her daughters from school. She said she saw a group of men armed with sticks and stones harassing and throwing stones at several 16- and 17-year-old girls, to stop them marching to Tahrir (Freedom) Square in Ta'izz, the city's main protest area. They told the girls their parents did not know how to raise them, and that by going to the square, they were inviting sexual harassment. The men injured 14 of the girls.

These attacks, along with state-sponsored discrimination and their families' shame, are not making it easy on Yemeni women who are speaking out. But for now, they continue to stand up for their rights. Two days after Saleh's statement denouncing female activists as un-Islamic, thousands took to the streets again, determined to show that they will not be silenced or sent home.

In the past, any mention of Yemen's women in the news media has usually been about two issues, neither of them positive. The first is that they are more likely than most women in the Middle East to die in childbirth, and the second that they are among the least empowered women in the world.

The second assumption has recently been shattered by the uprisings in Yemen.

Since the beginning of the protests, women like Karman have come out in great numbers to demonstrate against President Ali Abdullah Saleh, who has ruled in Yemen for more than 30 years. They have stood side by side with tens of thousands of Yemeni men to fill the city squares of Sana'a, Ta'izz, Aden, and other major cities, demanding his resignation.

Such has been the power of their presence that Saleh felt obliged to denounce women who join the protests as un-Islamic for demonstrating alongside men.

The protests have given women a chance to express their own concerns about their day-to-day struggles with the Saleh government, including their subordinate legal status as perpetual minors who require male guardians and the continued prevalence of harmful practices like child marriage.

Women have held their own demonstrations, but have also protested with their male counterparts, calling for democracy. Their courage has come at a cost: security forces and pro-government plain-clothes operators have threatened, verbally assaulted and attacked women protesters. At least 109 peaceful demonstrators or bystanders in Yemen have been killed since daily protests began in mid-February, and several hundred injured.

To be sure, many more male protesters have been targeted, but women in Yemen are particularly vulnerable to such attacks. Yemen is a traditional society, where women generally have low social status and are excluded from public life.

In 2010 a Freedom House report on women in the Middle East highlighted Yemen as one of only three countries in the region that had failed to make significant progress on women's rights in the preceding five years. Women have never held more than three seats out of 301 in the lower house of parliament. They do not have the same citizenship rights as men. And domestic violence is still not a criminal offence. Women's rights activists often face harassment.

In this context, many women are fearful about the consequences of participating in the uprising against Saleh. One young activist in Sana'a, who did not want to be named, told me she is one of several women she knows who don't tell their families they are going to the protests. She said the families have forbidden them from demonstrating, partly because they are worried about the women's safety, and partly because they know their reputations and honour are at stake.

The fears about their safety are not unfounded. On 27 April, unknown gunmen on motorcycles fired shots into the air outside the house of a prominent female activist, Bushra al-Maqtari, in Ta'izz, a city south of the capital. Maqtari said she had previously received anonymous verbal threats.

Another female activist from Ta'izz, a lawyer who also did not want to be named, told me about an incident she witnessed on 16 March when she went to pick up her daughters from school. She said she saw a group of men armed with sticks and stones harassing and throwing stones at several 16- and 17-year-old girls, to stop them marching to Tahrir (Freedom) Square in Ta'izz, the city's main protest area. They told the girls their parents did not know how to raise them, and that by going to the square, they were inviting sexual harassment. The men injured 14 of the girls.

These attacks, along with state-sponsored discrimination and their families' shame, are not making it easy on Yemeni women who are speaking out. But for now, they continue to stand up for their rights. Two days after Saleh's statement denouncing female activists as un-Islamic, thousands took to the streets again, determined to show that they will not be silenced or sent home.