As a teacher in Syria the writer saw the effect of Assad's culture of fear, but his regime is pandering to social sensibilities

By Joseph Willits

By Joseph Willits

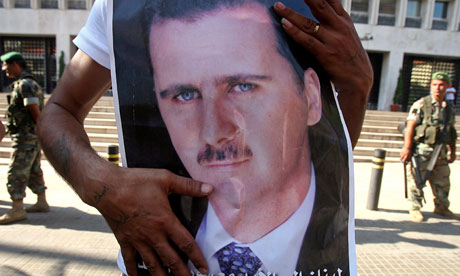

A protester holds a picture of Syrian president Bashar al-Assad during a demonstration in support of the regime held in Lebanon. Photograph: AFP/Getty Images

The events now happening in Syria seemed a remote prospect when I arrived to teach English at an international school in Homs last year. Even when regime change came to Tunisia and Egypt earlier this year, few expected anything of the kind to occur in Syria.

Looking at my students, I could scarcely imagine them as revolutionaries. They seemed so bound to the 40-year-old Ba'athist ideology, emasculated by the cult of Bashar al-Assad while monitored by social sensibilities.

In school each day, we pledged our allegiance to Ba'athism, to Assad and to a sense of unique Arab nationalism. One line of the national anthem always stuck with me: "Our den of Arabism is a sacred sanctuary."

Yes, Syria was a sanctuary. In this sanctuary's educational institutions dissent was frowned upon and a culture of fear flourished. What might revolution mean to these teenage Syrians, and how would they respond to it?

On the surface, for many of my students it would mean nothing. They were mostly from the top shelves of Syrian society – Alawite, Christian and Muslim – the products of politics and business rather than defined by sectarianism. Their hopes would lie mostly within the system and for them the struggle for bread was an alien prospect. A year later, though, the profiles of similar young Syrians are all over Facebook – some frightened, others more hopeful, proud, naively and deliberately deluded. Sometimes a black screen replaces a photo of them with friends, for anonymity, for mourning, or just out of caution, wisely hedging their bets. Other profiles feature a "pray for Homs" poster, or a picture of the president himself.

Their comments range from tentative to accusatory – directed at the "terrorists" who are said to be destroying Assad's Syria. One compares the sounds of shooting with the celebratory sounds of Eid in the early hours. Another remarks: "I simply cannot sleep."

Those who originally posted controversial, apparently anti-Assad sentiment, have withdrawn in fright. Their Facebook protests have become dormant and their daily facade is basketball, friends and Ba'athism. Their resistance, however, remains.

I would never have imagined, while teaching in Homs, and even in the beginning of protests in the city, that my students would become directly affected. Like the majority of my students, Ameen al-Khateeb was a declared fan of the president and his wife on Facebook, and proud to be Syrian.

"In Bashar we trust" was a dictum that resonated for him, yet the bullets of the regime hit his school bus, killing his 10-year-old sister. Still he appears loyal to the president, as do many others, but a wariness of online activity and dissent has encouraged more engagement in street protests.

The culture of fear, which generations of Syrians have grown up with, can never be underestimated. Assad's speech on 20 June, heaping blame upon foreign "saboteurs", angered so many, prompting more protests, yet reassured others with familiar statements. Those who were brave protested on the streets; those who were fearful maintained their silence, perhaps waiting for the tide to blow over.

I questioned an Alawite friend of mine about the situation in Homs when serious protests first began. "You know we live in a peaceful country," she said, accusing al-Jazeera of heading a media ambush against the regime. Her words, like those in Assad's speech, and so many I knew in Homs, simply echoed one another and the party line. I knew Syria was peaceful; a wonderful example of a prison camp fit for tourists, teachers and Lawrence of Arabia wannabes – and all overlooked by images of Assad in various poses.

As I walked daily around the streets my eyes were always drawn to the posters of the regime's propaganda, mesmerised myself by the cult of Assad. I quickly learned the boundaries of conversations about the president.

My joking insinuation that Assad could be my lookalike if I only had a moustache sparked controversy. Foreigners are told to be careful when mentioning the president, since any hint of disrespect can be construed as mocking and spiteful. In an attempt to relate to and share with my students, I told them that both Asma al-Assad (the president's wife) and I attended King's College London. This was met with deathly silence – as if I had been trying to put myself on a par with her.

In a sense, however, I felt that the cult of Assad disguised the real issue – that Syria was a society made up of various and contrasting social sensibilities, heavily exploited by the Ba'athist regime.

In Damascus, over the past five years, an arts scene had begun to flourish, and yet a performance of Romeo and Juliet was censored at a school in Homs: on stage, the loving couple looked at one another gormlessly, their kiss having been taken away from them. In this case it wasn't Ba'athism stifling expression, but society itself.

Through education the regime could both pander to social sensibilities and alienate the more socially conservative elements. Those who displayed symbols of faith, contrary to the regime's secular image, could become targets. A colleague of mine (choosing to wear the hijab, against the wishes of her exiled father who recognised the implications of this symbol) became the subject of gossip, initiated by the school itself.

Fears of the Muslim Brotherhood and paranoia stemming from the 1982 massacre in Hama were seemingly ingrained into the Ba'athist machine. Students are still being taught to fear repercussions. In Hama in 1982, internet dissent was not an issue. In Homs today, teenage Syrians are logging on, sometimes as themselves, sometimes as products of the regime – mostly we shall never know which.

I cannot condemn those who put pictures of Assad on to Facebook, whether out of pride or self-preservation, nor can I demand that the revolutionaries of whatever cause come clean and stand tall. I was there, among them. I know how it feels.

-This commentary was published in The Guardian on 01/07/2011

- Joseph Willits spent a significant time teaching in Syria. He studied English literature at King's College London, focusing on perceptions of Persia and the Middle East in travel writing of the early modern period

- Joseph Willits spent a significant time teaching in Syria. He studied English literature at King's College London, focusing on perceptions of Persia and the Middle East in travel writing of the early modern period

No comments:

Post a Comment