By Hassan Hassan

In 2003, on my way from Damascus to my hometown in eastern Syria, near the Iraq border, my driver offered to drop me off at a border point where Syrian fighters were taken to join the Iraqi insurgency. I couldn't believe that Syria's secular, Baathist regime was allowing fighters to cross the border to engage in the Iraqi "jihad" against the US-led invasion.

My driver insisted this was the case, and thus the offer to show me the border crossing. He said there was a fleet of drivers who made a living by picking up young men in the Syrian city of Al Bukamal and taking them to the city of Al Qaim, which lies directly across the border with Iraq. It was unclear, my driver said, who handled these young aspiring fighters after that point.

I remained sceptical until I reached home. There, I learnt that two of my distant relatives had already left for Iraq to join the insurgency.

"The government is encouraging it," my driver told me, with excitement, during that ride in 2003. In Syria, at least before the uprising broke out last year, taxi drivers were widely believed to work for the regime's intelligence services.

He proved to be correct. At the time, young men from across Syria were travelling east across the border. Those who crossed using public transport, mainly from Al Bukamal, were usually sent back. Others who travelled with experienced smugglers later said that they had made it all the way to Fallujah.

The issue of the Syrian regime's involvement in terrorist activities in Iraq after 2003 has been raised again by Nawaf Al Fares, the former Syrian ambassador to Baghdad who recently defected. In the past two weeks, Mr Al Fares has said Damascus encouraged young men to join Al Qaeda in Iraq. Given the situation now in Syria, the issue merits another look.

After the invasion of Iraq, the Damascus University campus was flooded with whispers suggesting that Baghdad might soon fall, and that many Syrians would go to fight the Americans. The rumours went viral. No one knew who planted the idea, but it quickly spread among the students. In retrospect, it showed the power of the regime to render youth enthusiasm into an ingredient of terrorism.

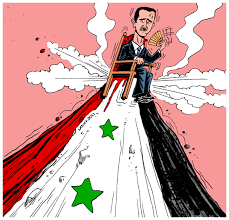

The Baath party was founded in Syria in 1947 on a pan-Arabist platform with the stated goals of unity, freedom and socialism. "Freedom" in this sense, it is important to note, meant freedom from colonialism, not personal liberty. But the definition lost its meaning as the regimes in Syria, starting in 1963, and Iraq, 1968 to 2003, solidified into strongarm dictatorships.

The poison of the modern-day Baathist regime is not only its willingness to torture and kill its own population. It is far more insidious. There is an ideology that breeds violence and extremism, a tendency that has not been sufficiently examined. In examining Middle East militancy and terrorism, academics have focused on religious extremism and often overlooked other ideologies.

There was a striking commonality among many young Syrians who went to join the insurgency in Iraq. Accounts from men who went to fight, or from their friends and families, often told that they were not particularly religious. That was true for my two relatives (incidentally, both had been involved in petty crime). Yet they had gone to fight - one of them later claimed he had taken part in the so-called "airport battle" in Baghdad, in which it was widely believed that Saddam Hussein had led the fight against the Americans in the early days of the war.

Neither of my relatives has joined the armed resistance in the current uprising against the Syrian regime, although FSA-affiliated groups operate in their town. Another man from Deraa who had fought in Iraq, and was recently killed during anti-regime protests, had - tellingly - chosen to protest peacefully and also had declined to join the Free Syrian Army. His cousin, who had accompanied him to Iraq, has to date also limited himself to peaceful protests. Other former fighters in Iraq have joined the armed resistance, but many have not.

Obviously, not all of the men who joined the insurgency in Iraq were religious extremists. If they were, they would presumably be fighting the secular regime in Damascus. Many of those who have chosen to pick up arms against the Syrian regime did so because they or their families have directly suffered at the hands of the regime.

In 2006, I saw another example of the pervasive influence of the ideology's incitement to violence. Crowds of Syrians burnt the Danish and Norwegian embassies in Damascus in 2006 after the publication of cartoons depicting the Prophet Mohammed. One of the mob leaders related the event to me later - but I knew this man. He was a "lifestyle liberal", in the sense that he was not a practising Muslim, drank alcohol and had sex outside of marriage. He spoke in the language of the regime, almost certainly acting on his own but inspired by the Baathist ideology. (The Syrian regime was later accused of orchestrating the embassy arsons in Damascus and Beirut.)

There are many religious extremists who choose not to fight; others who choose to fight are not religious. The Baathist ideology has exploited sentiments - cultural, economic, social and sometimes religious - to incite violence for political gain. As a radical ideology that requires complete social, political and cultural transformation, there is an inevitable propensity for violence.

Despite the Baathist regime's brutality in Syria, some intellectuals still argue that these acts of violence are anomalies. Is it chance that the Baathist rulers - Saddam Hussain, Hafez Al Assad and his son - all shelled cities, terrorised, tortured and killed their people? This ideology needs to be understood if its legacy is to be rejected. It is not enough for the regime to fall.

-This commentary was first published in The National on 26/07/2012

In 2003, on my way from Damascus to my hometown in eastern Syria, near the Iraq border, my driver offered to drop me off at a border point where Syrian fighters were taken to join the Iraqi insurgency. I couldn't believe that Syria's secular, Baathist regime was allowing fighters to cross the border to engage in the Iraqi "jihad" against the US-led invasion.

My driver insisted this was the case, and thus the offer to show me the border crossing. He said there was a fleet of drivers who made a living by picking up young men in the Syrian city of Al Bukamal and taking them to the city of Al Qaim, which lies directly across the border with Iraq. It was unclear, my driver said, who handled these young aspiring fighters after that point.

I remained sceptical until I reached home. There, I learnt that two of my distant relatives had already left for Iraq to join the insurgency.

"The government is encouraging it," my driver told me, with excitement, during that ride in 2003. In Syria, at least before the uprising broke out last year, taxi drivers were widely believed to work for the regime's intelligence services.

He proved to be correct. At the time, young men from across Syria were travelling east across the border. Those who crossed using public transport, mainly from Al Bukamal, were usually sent back. Others who travelled with experienced smugglers later said that they had made it all the way to Fallujah.

The issue of the Syrian regime's involvement in terrorist activities in Iraq after 2003 has been raised again by Nawaf Al Fares, the former Syrian ambassador to Baghdad who recently defected. In the past two weeks, Mr Al Fares has said Damascus encouraged young men to join Al Qaeda in Iraq. Given the situation now in Syria, the issue merits another look.

After the invasion of Iraq, the Damascus University campus was flooded with whispers suggesting that Baghdad might soon fall, and that many Syrians would go to fight the Americans. The rumours went viral. No one knew who planted the idea, but it quickly spread among the students. In retrospect, it showed the power of the regime to render youth enthusiasm into an ingredient of terrorism.

The Baath party was founded in Syria in 1947 on a pan-Arabist platform with the stated goals of unity, freedom and socialism. "Freedom" in this sense, it is important to note, meant freedom from colonialism, not personal liberty. But the definition lost its meaning as the regimes in Syria, starting in 1963, and Iraq, 1968 to 2003, solidified into strongarm dictatorships.

The poison of the modern-day Baathist regime is not only its willingness to torture and kill its own population. It is far more insidious. There is an ideology that breeds violence and extremism, a tendency that has not been sufficiently examined. In examining Middle East militancy and terrorism, academics have focused on religious extremism and often overlooked other ideologies.

There was a striking commonality among many young Syrians who went to join the insurgency in Iraq. Accounts from men who went to fight, or from their friends and families, often told that they were not particularly religious. That was true for my two relatives (incidentally, both had been involved in petty crime). Yet they had gone to fight - one of them later claimed he had taken part in the so-called "airport battle" in Baghdad, in which it was widely believed that Saddam Hussein had led the fight against the Americans in the early days of the war.

Neither of my relatives has joined the armed resistance in the current uprising against the Syrian regime, although FSA-affiliated groups operate in their town. Another man from Deraa who had fought in Iraq, and was recently killed during anti-regime protests, had - tellingly - chosen to protest peacefully and also had declined to join the Free Syrian Army. His cousin, who had accompanied him to Iraq, has to date also limited himself to peaceful protests. Other former fighters in Iraq have joined the armed resistance, but many have not.

Obviously, not all of the men who joined the insurgency in Iraq were religious extremists. If they were, they would presumably be fighting the secular regime in Damascus. Many of those who have chosen to pick up arms against the Syrian regime did so because they or their families have directly suffered at the hands of the regime.

In 2006, I saw another example of the pervasive influence of the ideology's incitement to violence. Crowds of Syrians burnt the Danish and Norwegian embassies in Damascus in 2006 after the publication of cartoons depicting the Prophet Mohammed. One of the mob leaders related the event to me later - but I knew this man. He was a "lifestyle liberal", in the sense that he was not a practising Muslim, drank alcohol and had sex outside of marriage. He spoke in the language of the regime, almost certainly acting on his own but inspired by the Baathist ideology. (The Syrian regime was later accused of orchestrating the embassy arsons in Damascus and Beirut.)

There are many religious extremists who choose not to fight; others who choose to fight are not religious. The Baathist ideology has exploited sentiments - cultural, economic, social and sometimes religious - to incite violence for political gain. As a radical ideology that requires complete social, political and cultural transformation, there is an inevitable propensity for violence.

Despite the Baathist regime's brutality in Syria, some intellectuals still argue that these acts of violence are anomalies. Is it chance that the Baathist rulers - Saddam Hussain, Hafez Al Assad and his son - all shelled cities, terrorised, tortured and killed their people? This ideology needs to be understood if its legacy is to be rejected. It is not enough for the regime to fall.

-This commentary was first published in The National on 26/07/2012

No comments:

Post a Comment