By Sean Kane

Libya's elections did not need to be perfect, but the country plainly needs a popularly elected government to tackle the difficult and unpopular decisions involved in building the new state. The polls thus could have been judged a success merely by taking place without major disruption, a test they aced with flying colors following reports of 65 percent turnout and over 98 percent of polling centers opening without incident. Around the country, the long-awaited vote was justifiably treated as cause for national celebration.

But the seeds for political contention at the next stage may have been sown in the run-up to the polls. Less than 48 hours prior to elections, the National Transitional Council (NTC) stripped the to be elected national congress of its core mandate: supervising the drafting of Libya's new constitution. Rather than being appointed by the new congress, the constitutional commission actually drafting the charter will theoretically now be directly elected in a second set of polls that give all parts of the country equal representation. This legal bombshell risks acrimony later this year between different parts of the country as well as rejection by the newly ascendant political parties, who on paper find themselves in charge of a congress suddenly relegated to bystander status on constitutional matters.

A Libyan proverb has it that "laws are made in Tripoli, observed in Misrata and die in Benghazi." It captures Tripoli's status as the seat of government, the highly organized nature of the commercial port city of Misrata, and the hotbed of activism that is Benghazi. True to form, as a long-running center of opposition to Qaddafi's rule, Benghazi was the birthplace of the Libyan revolution. It should not then be a surprise that the city sees itself as the watchdog of the revolution and the new authorities in Tripoli.

Normally the vigilance of Benghazi is a healthy thing, helping the country avoid a return to the excessive concentration of power and wealth in Tripoli that marked the Qaddafi regime. But somewhere in the last few months Benghazi took a wrong turn. Following the revolution it was the most stable and institutionally advanced city in Libya, but now residents describe it as increasingly troubled. The city has become a locus of aggressive street actions by federalism supporters, seemingly politically motivated assassinations, and had its international presence targeted by small groups of Islamist militants. Underlying all of this is a deep current of resentment of the more wealthy and populous Tripoli.

Libya has of course been no stranger to unrest since the triumph of its revolution in October, 2011. But what is happening in Benghazi is qualitatively different. Other clashes around the country have generally been micro-conflicts, locally contained and concerned with parochial issues rather than larger ideology or proposed alternatives to the new order.

This is not the case among backers of an Islamic emirate or with the harder core of federalism supporters in eastern Libya. The latter include the self-declared Barqa Council (Barqa is the Arabic name for Libya's eastern region), who periodically threaten separation from the rest of the country. Both groups have been willing to go outside of the political process to pursue their respective visions. And while high electoral turnout in the East was an emphatic demonstration that neither faction has widespread support, both have shown an ability to exploit broader regional feelings of maltreatment to act as violent spoilers.

Fringe Islamic militants are thought to be behind a spate of recent bombings of diplomatic and humanitarian offices in Benghazi and graffiti has sprung up in the conservative eastern city of Derna warning that "Elections = bombings." Meanwhile, suspected sympathizers of the Barqa Council unsuccessfully attempted to enforce its call for an electoral boycott by ransacking and setting fire to election centers in two eastern cities and shooting down a Libyan air force helicopter that was carrying electoral supplies to Benghazi.

The task that confronts the newly elected government is to neuter these spoilers by taking advantage of the opportunity provided by eastern Libyans' literal vote of confidence in the political process. This can best be achieved by separating out and transparently addressing legitimate anxieties in eastern Libya about marginalization from more extreme demands. Benghazi cannot realistically expect to regain the status it held as Libya's revolutionary capital and a center of worldwide attention last year, but it and other parts of the country's periphery should be more integrated into national political decision-making, government administration, and economic planning.

A proactive approach is now required to break the pattern set by the NTC of only making significant concessions to Eastern opinion following provocative actions by the Barqa Council in particular. (These include a unilateral declaration of an autonomous Eastern region in March and armed attempts to blockade election materials from reaching the East over the last month). Continuing a reactive policy, as seen in the NTC's dramatic last minute move reopening the basic tenets of the country's constitutional roadmap would seem to reward and invite further pressure tactics and militancy.

The key political issue that the Barqa Council has been able to agitate around is the representation of eastern Libya in the 200-person national congress. Arguing that a congress supervising the writing of a constitution is different from an ordinary parliament, the East has held that each of Libya's three geographic regions should have equal representation in the body despite the western region of Tripolitania making up two-thirds of the country's population. The issue has become the shorthand by which the Eastern region as a whole -- not just Barqa supporters --evaluates its position in the new Libyan political constellation.

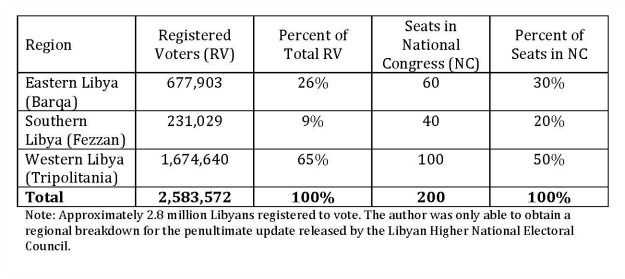

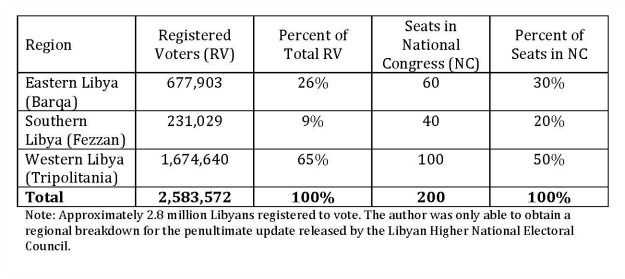

Widespread eastern dissatisfaction with the 60 seats for their region ultimately received in the national congress (especially compared to 100 for Tripoli) was used by the Barqa Council as a jumping off point for its calls for eastern Libya to go its own way. The irony is that the distribution of the seats, tortuously negotiated within the NTC based on Libya's contested 2006 population census, appear in hindsight to be quite reasonable. Take a look at the seats for each region as compared to the number of people who actually turned up to register to vote this May:

Benghazi and eastern Libya, in fact, received a slight bump in representation over its share of registered voters. More significantly, western Libya took a substantial haircut as compared to its presumed population weight (mainly to the benefit of the perennially overlooked south of Libya). This compromise seat allocation recognizes Tripoli's preponderance in population but also acknowledges Benghazi's fear that a super-majority for western Libya in the national congress could have enabled it to steamroll the other regions in the writing of the constitution.

So what exactly is the problem? How has this seat allocation fed such unrest in and around Benghazi? Part of the answer is that symbolism matters. The seat allocation was negotiated behind closed doors in luxury Tripoli hotels, directly playing into the insecurities of easterners living over a thousand kilometers away. More substantively, it is possible that the debate became too caught up in a zero-sum tug of war over seat numbers. Recall that the underlying eastern concern is Tripoli being left unchecked to constitutionally recreate Qaddafi's centralism. One way to address this is to equally distribute seats in the national congress.

But it is not the only way. There are a plethora of complementary safeguards that could have been put in place to avoid a purported tyranny of a western Libya majority. These include requiring two-thirds majorities on key constitutional decisions by the national congress and inclusive agreement on a statement of principles that the constitutional commission must observe in preparing the text.

The NTC had access to a wealth of international expert advice on the organization of elections, including access to best practice on seat allocation methods. But the international community is not as well mobilized to provide technical advice on procedural options for writing constitutions. Libyans see the elections and constitution stage as flowing together, but were only really getting detailed technical advice on the former. This might partially explain why the NTC was able to develop a sound technical compromise on allocating electoral seats while its efforts to recast the constitutional process were more maladroit and set up a post election political stand-off.

Last week's surprise from the NTC serves as a fitting coda to its somewhat chaotic post-revolutionary turn in office. To be fair, the council justified the decision as necessary to preserve the peace on election day in Benghazi. Who is to say they were wrong? The decision was undoubtedly well received in the East, even if it is impractical to quickly organize a second round of elections for a constitutional commission. But as the euphoria of voting fades, any effort to walk back the order will likely be seen in the East as taking something away something them. This could create fertile ground for further agitation by federalists or even Islamic militants.

Yet an attempt to repeal is almost certain. Senior officials in Mahmoud Jibril's National Forces Alliance, the early leader in election returns, and the Muslim Brotherhood's Justice and Building Party previously told me that they were not running to merely head a coalition government scheduled to be dissolved in a matter of months. Rather the prize was to shape the constitution. Along with political actors from western Libya, they were explicit that once the national congress is seated they will push to reverse any weakening of the body's supervisory role over the constitutional process.

What happens next, as it has been all along, will be a decidedly Libyan matter. As a government official explained to me after the NTC first attempted to reshuffle the constitutional deck back in March: "don't take this as the final word, all the council has done is signal that the roadmap is now up for negotiation." With the NTC effectively hitting the reset button on the entire constitutional process on its way out the door, this is now truer than ever.

Fortunately, the rousing success of the elections provides an opportunity to reimagine the constitutional framework and get it right. The winning political parties received electoral endorsement across the country, and are well situated to intermediate regional expectations. Likewise, the Barqa Council has been chastened by the strong public will to vote displayed in the East. Jibril's extension of an invitation to dialogue with federalists and other easterners, whom he described as "patriots" that "care about Libya," is a positive early sign. The international community should support such dialogue by producing a comprehensive menu of technical options so Libyans can consider the range of ways in which the national congress and constitutional commission can relate to each other and take decisions that factor in Libya's political geography.

Addressing diffuse feelings of resentment in the East and getting the region fully vested in rule-bound democratic politics is certainly a wider challenge than just technical arrangements for drafting the constitution. More far-reaching inter-regional dialogue will be required. Also necessary is a strong interim government willing to provide symbolic reassurances such as perhaps placing ministries in the East or launching high-profile infrastructure projects to counter strongly held regional feelings of marginalization. But getting an accepted constitutional drafting configuration in place is the first item on the national congress' docket, and if this doesn't happen, the prospects for broader rapprochement will surely suffer.

-This commentary was first published in Foreign Policy on 12/07/2012

-Sean Kane is a Truman Security Fellow. From November 2011 to May 2012 he lived in Benghazi and worked with Libyans on promoting conflict resolution

Libya's elections did not need to be perfect, but the country plainly needs a popularly elected government to tackle the difficult and unpopular decisions involved in building the new state. The polls thus could have been judged a success merely by taking place without major disruption, a test they aced with flying colors following reports of 65 percent turnout and over 98 percent of polling centers opening without incident. Around the country, the long-awaited vote was justifiably treated as cause for national celebration.

But the seeds for political contention at the next stage may have been sown in the run-up to the polls. Less than 48 hours prior to elections, the National Transitional Council (NTC) stripped the to be elected national congress of its core mandate: supervising the drafting of Libya's new constitution. Rather than being appointed by the new congress, the constitutional commission actually drafting the charter will theoretically now be directly elected in a second set of polls that give all parts of the country equal representation. This legal bombshell risks acrimony later this year between different parts of the country as well as rejection by the newly ascendant political parties, who on paper find themselves in charge of a congress suddenly relegated to bystander status on constitutional matters.

A Libyan proverb has it that "laws are made in Tripoli, observed in Misrata and die in Benghazi." It captures Tripoli's status as the seat of government, the highly organized nature of the commercial port city of Misrata, and the hotbed of activism that is Benghazi. True to form, as a long-running center of opposition to Qaddafi's rule, Benghazi was the birthplace of the Libyan revolution. It should not then be a surprise that the city sees itself as the watchdog of the revolution and the new authorities in Tripoli.

Normally the vigilance of Benghazi is a healthy thing, helping the country avoid a return to the excessive concentration of power and wealth in Tripoli that marked the Qaddafi regime. But somewhere in the last few months Benghazi took a wrong turn. Following the revolution it was the most stable and institutionally advanced city in Libya, but now residents describe it as increasingly troubled. The city has become a locus of aggressive street actions by federalism supporters, seemingly politically motivated assassinations, and had its international presence targeted by small groups of Islamist militants. Underlying all of this is a deep current of resentment of the more wealthy and populous Tripoli.

Libya has of course been no stranger to unrest since the triumph of its revolution in October, 2011. But what is happening in Benghazi is qualitatively different. Other clashes around the country have generally been micro-conflicts, locally contained and concerned with parochial issues rather than larger ideology or proposed alternatives to the new order.

This is not the case among backers of an Islamic emirate or with the harder core of federalism supporters in eastern Libya. The latter include the self-declared Barqa Council (Barqa is the Arabic name for Libya's eastern region), who periodically threaten separation from the rest of the country. Both groups have been willing to go outside of the political process to pursue their respective visions. And while high electoral turnout in the East was an emphatic demonstration that neither faction has widespread support, both have shown an ability to exploit broader regional feelings of maltreatment to act as violent spoilers.

Fringe Islamic militants are thought to be behind a spate of recent bombings of diplomatic and humanitarian offices in Benghazi and graffiti has sprung up in the conservative eastern city of Derna warning that "Elections = bombings." Meanwhile, suspected sympathizers of the Barqa Council unsuccessfully attempted to enforce its call for an electoral boycott by ransacking and setting fire to election centers in two eastern cities and shooting down a Libyan air force helicopter that was carrying electoral supplies to Benghazi.

The task that confronts the newly elected government is to neuter these spoilers by taking advantage of the opportunity provided by eastern Libyans' literal vote of confidence in the political process. This can best be achieved by separating out and transparently addressing legitimate anxieties in eastern Libya about marginalization from more extreme demands. Benghazi cannot realistically expect to regain the status it held as Libya's revolutionary capital and a center of worldwide attention last year, but it and other parts of the country's periphery should be more integrated into national political decision-making, government administration, and economic planning.

A proactive approach is now required to break the pattern set by the NTC of only making significant concessions to Eastern opinion following provocative actions by the Barqa Council in particular. (These include a unilateral declaration of an autonomous Eastern region in March and armed attempts to blockade election materials from reaching the East over the last month). Continuing a reactive policy, as seen in the NTC's dramatic last minute move reopening the basic tenets of the country's constitutional roadmap would seem to reward and invite further pressure tactics and militancy.

The key political issue that the Barqa Council has been able to agitate around is the representation of eastern Libya in the 200-person national congress. Arguing that a congress supervising the writing of a constitution is different from an ordinary parliament, the East has held that each of Libya's three geographic regions should have equal representation in the body despite the western region of Tripolitania making up two-thirds of the country's population. The issue has become the shorthand by which the Eastern region as a whole -- not just Barqa supporters --evaluates its position in the new Libyan political constellation.

Widespread eastern dissatisfaction with the 60 seats for their region ultimately received in the national congress (especially compared to 100 for Tripoli) was used by the Barqa Council as a jumping off point for its calls for eastern Libya to go its own way. The irony is that the distribution of the seats, tortuously negotiated within the NTC based on Libya's contested 2006 population census, appear in hindsight to be quite reasonable. Take a look at the seats for each region as compared to the number of people who actually turned up to register to vote this May:

Benghazi and eastern Libya, in fact, received a slight bump in representation over its share of registered voters. More significantly, western Libya took a substantial haircut as compared to its presumed population weight (mainly to the benefit of the perennially overlooked south of Libya). This compromise seat allocation recognizes Tripoli's preponderance in population but also acknowledges Benghazi's fear that a super-majority for western Libya in the national congress could have enabled it to steamroll the other regions in the writing of the constitution.

So what exactly is the problem? How has this seat allocation fed such unrest in and around Benghazi? Part of the answer is that symbolism matters. The seat allocation was negotiated behind closed doors in luxury Tripoli hotels, directly playing into the insecurities of easterners living over a thousand kilometers away. More substantively, it is possible that the debate became too caught up in a zero-sum tug of war over seat numbers. Recall that the underlying eastern concern is Tripoli being left unchecked to constitutionally recreate Qaddafi's centralism. One way to address this is to equally distribute seats in the national congress.

But it is not the only way. There are a plethora of complementary safeguards that could have been put in place to avoid a purported tyranny of a western Libya majority. These include requiring two-thirds majorities on key constitutional decisions by the national congress and inclusive agreement on a statement of principles that the constitutional commission must observe in preparing the text.

The NTC had access to a wealth of international expert advice on the organization of elections, including access to best practice on seat allocation methods. But the international community is not as well mobilized to provide technical advice on procedural options for writing constitutions. Libyans see the elections and constitution stage as flowing together, but were only really getting detailed technical advice on the former. This might partially explain why the NTC was able to develop a sound technical compromise on allocating electoral seats while its efforts to recast the constitutional process were more maladroit and set up a post election political stand-off.

Last week's surprise from the NTC serves as a fitting coda to its somewhat chaotic post-revolutionary turn in office. To be fair, the council justified the decision as necessary to preserve the peace on election day in Benghazi. Who is to say they were wrong? The decision was undoubtedly well received in the East, even if it is impractical to quickly organize a second round of elections for a constitutional commission. But as the euphoria of voting fades, any effort to walk back the order will likely be seen in the East as taking something away something them. This could create fertile ground for further agitation by federalists or even Islamic militants.

Yet an attempt to repeal is almost certain. Senior officials in Mahmoud Jibril's National Forces Alliance, the early leader in election returns, and the Muslim Brotherhood's Justice and Building Party previously told me that they were not running to merely head a coalition government scheduled to be dissolved in a matter of months. Rather the prize was to shape the constitution. Along with political actors from western Libya, they were explicit that once the national congress is seated they will push to reverse any weakening of the body's supervisory role over the constitutional process.

What happens next, as it has been all along, will be a decidedly Libyan matter. As a government official explained to me after the NTC first attempted to reshuffle the constitutional deck back in March: "don't take this as the final word, all the council has done is signal that the roadmap is now up for negotiation." With the NTC effectively hitting the reset button on the entire constitutional process on its way out the door, this is now truer than ever.

Fortunately, the rousing success of the elections provides an opportunity to reimagine the constitutional framework and get it right. The winning political parties received electoral endorsement across the country, and are well situated to intermediate regional expectations. Likewise, the Barqa Council has been chastened by the strong public will to vote displayed in the East. Jibril's extension of an invitation to dialogue with federalists and other easterners, whom he described as "patriots" that "care about Libya," is a positive early sign. The international community should support such dialogue by producing a comprehensive menu of technical options so Libyans can consider the range of ways in which the national congress and constitutional commission can relate to each other and take decisions that factor in Libya's political geography.

Addressing diffuse feelings of resentment in the East and getting the region fully vested in rule-bound democratic politics is certainly a wider challenge than just technical arrangements for drafting the constitution. More far-reaching inter-regional dialogue will be required. Also necessary is a strong interim government willing to provide symbolic reassurances such as perhaps placing ministries in the East or launching high-profile infrastructure projects to counter strongly held regional feelings of marginalization. But getting an accepted constitutional drafting configuration in place is the first item on the national congress' docket, and if this doesn't happen, the prospects for broader rapprochement will surely suffer.

-This commentary was first published in Foreign Policy on 12/07/2012

-Sean Kane is a Truman Security Fellow. From November 2011 to May 2012 he lived in Benghazi and worked with Libyans on promoting conflict resolution

No comments:

Post a Comment